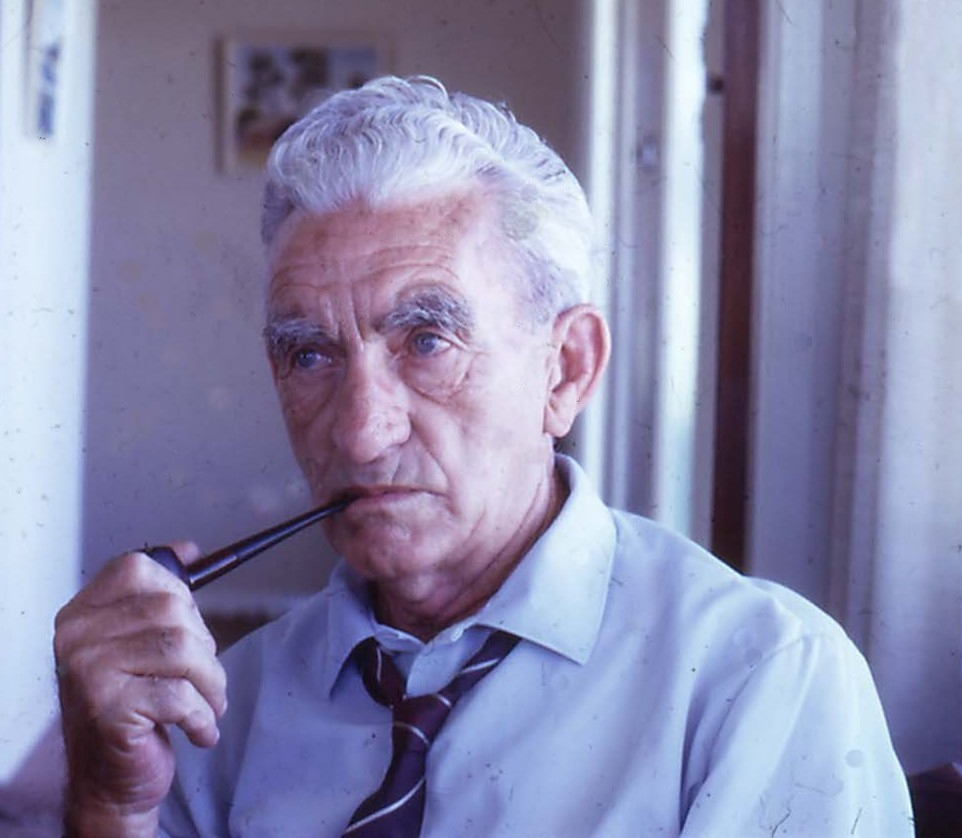

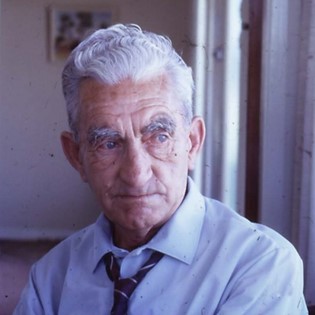

I Was Just Thinking: The Memoirs of William Edward Mercer 1898-1983

Foreword

These memoirs recount the life of William Edward Mercer, his childhood spent mostly in the small town of Great Harwood in Lancashire, his service in the Royal Army Medical Corps, his return home and his migration to Australia.

Being an adventurous young man he voiced his intentions to join the RAMC when he was old enough, so he was encouraged by a local doctor to lie about his age and go off to war. He tells how he travelled to Turkey, the Middle East and India describing the sights and the people he met, and his escapades along the way. When he arrived home to Great Harwood at the end of the war he realised that by now he was out of step with his home town and the people he had left behind. Many of his own friends had moved on, as had some of his family and his life lacked purpose and excitement.

He eventually met and married his lifelong partner Eda, and they were encouraged by her aunt to travel to Australia and begin a new life together. His tale continues as they cross the ocean and see new places and sights along the way. Eventually arriving in the land that would be their home, they embark on a pioneering journey of ups and downs from building a home, finding work and raising a family.

Throughout the book William is a likeable, affable character who has a natural way of storytelling. We hope you will enjoy reading it and travelling along on his life’s journey from Great Harwood, his wartime tales and his years in Australia, as much as we have enjoyed being allowed to produce it.

In 2009 William Mercer’s grandson Steve and his family visited Great Harwood from Australia. Leonie, Steve’s wife, presented Great Harwood History Society with copies of these memoirs that William had written for his grandchildren, which she had transcribed and produced in a book form along with a collection of pictures. GHHS decided that these memoirs were worthy of a wider audience and contacted the family to ask permission to republish them in an edited format for a more general public. Sadly, we discovered that Leonie had died, but the family consented to allow the publication of the edited book in her memory. A percentage of the proceeds of the sales was donated to a charity in remembrance of her.

GHHS

I was just thinking…

… and I remember when I was very young sitting on a small stool beside the fireplace jamb listening to my grandmother telling stories about her grandfather; he must have been a young man in about the year 1800. He was pressed from a dance hall in Preston; navy press gangs used to wander around the ports pressing any likely young men into the royal navy, and they were in the navy for the rest of their useful lives.

He must have been in many foreign places. He told her they used to catch monkeys by putting sugar in a small barrel, leaving the bunghole open. The monkeys would slip their hands through the bunghole, grab a handful of sugar but couldn’t pull the full fist out because the hole was too small, then they shot them. They probably did that because the monkeys were mischievous.

He must also have been in the naval battles in the Napoleonic War. He told her about Frenchmen being in the sea, trying to climb aboard the British ship (they had probably sunk a French ship), and saying, ‘We cut their bloody hands off’. Those were the days of wooden ships and iron men. They had to be tough to survive.

There were many more stories, which I have forgotten. All this led me to think how interesting it would have been if he had kept a diary or written something about his times (he probably would not have been able to write). Something from the ordinary sailor’s point of the view which would have been unique. All this again led me to think what will our grandchildren and their grandchildren think about our times: 1898-1968.

My early years

When we were born most transport was by horse-drawn vehicles. There were railways but the motorcar and the airplane were in the experimental stage. Motion pictures were only shown in travelling shows and were known as the ‘flicks’ because of the jerky and flickering movements of the actors. They were silent; commentators were employed to explain the story of the film. Later they tried to synchronise gramophone records with the film. This was a failure. I remember my grandmother saying, ‘They will never make them talk’. I wonder what she would have thought of television. Magic!

My very first memory was of my father handing to me a plucked fowl and saying, ‘Take that to your Mam’. This happened behind the local public house, which wasn’t far from where we lived. I don’t remember delivering it or anything else about it. Why this little incident stuck in my memory, I have no idea, but I have heard of other people remembering little incidents like this, which happened when they were very young. I must have been about three years of age. My only memory of my mother was when she was dead. I was in my father’s arms and I said, ‘She is on a board’. This board was part of the laying-out process before they put the corpse in the coffin. My mother must have had some nervous complaint; I was told later that they laid straw in the street in front of the house because she couldn’t stand the noise of the carts rattling over the cobblestones.

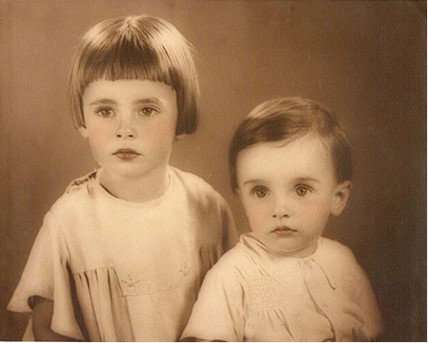

My mother died when I was about three years old and my younger sister about three months old. So we don’t remember her at all. We went to live with my father’s mother. My paternal grandmother lived in a little stone cottage at 54 Delph Road, Great Harwood; the walls were eighteen inches thick and covered with ivy. The date on the doorjamb was 1828.

My maternal Grandmother

Not very long after my mother died, my father must have taken me to Oldham, a town in south Lancashire, to my maternal grandmother. She was an Irishwoman having been born on Achill Island, which I believe is the furthermost western point in Ireland. I was told later that she had migrated from there when about sixteen to go in to service in Wicklow, which I think is on the eastern side of Ireland. From there, she went across the sea to Liverpool, where she probably met and married David Jones, my grandfather.

David Jones was a blacksmith. He died before I was born, but there was much evidence of him in my grandmother’s home. She had a copy of the famous picture ‘Shoeing the Bay Mare’, a picture of a blacksmith shoeing a mare and a donkey standing patiently at one side, in the glow of the furnace. It was a very good copy, oil on canvas, but unframed. I have seen a print of the original.

All his tools were there, hammers and tongs, and knives of peculiar shapes for paring horse hooves, and a branding iron which puzzled me for a long time, the ‘D Jones’ being the wrong way about. Later it was quite obvious that the branding iron was held on the hot steel and struck with a hammer which brought the ‘D Jones’ the right way about on his work.

Grandmother had a small wooden anvil which, when the top was taken off, was a trinket box. Grandfather had the wanderlust and often walked out of the house to disappear for weeks or months, leaving the family to their own devices. On one occasion he was away for three years; he went over to Canada to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. After three years, he walked into the house, as though he had just been down the street.

I must have inherited some of his wanderlust; I was told that I was twice picked up at the police station, a ‘lost child’, and that I was entertaining the policemen while they were feeding me with hot soup. The police station was about two miles from where I lived, so I must have walked through the heart of the city. I don’t remember anything about it.

When my grandfather died he left my grandmother in poor circumstances, with two sons and two daughters. The younger daughter was my mother who was a velvet weaver and the elder daughter was a lady’s maid at some place. The two sons were teenagers when I went to live with them. My grandmother took in boarders to make ends meet. One of these boarders was an Irishman, who was probably drunk when he let me fall from his knee. I fell with my head on to the knob of a damper (the damper was a drawplate, which when pulled out allowed a draught to go under the oven for cooking). My skull was fractured and I can still feel the indent in my forehead to this day.

I can remember sitting on the kerb outside my grandmother’s house, in petticoats and a little fur coat with a bandage around my head. In those days little boys wore petticoats until they were about five years old. When they were put into trousers, it was called being ‘breeched’ and it was quite an occasion, and called for a celebration. I liked being at grandmother’s house because I was allowed to run wild.

I remember standing at the corner of the street with other boys, we had what we called winter warmers, which consisted of a tobacco tin stuffed with raw cotton, of which there was plenty in Lancashire; the cotton was set alight and we blew through the holes in the sides till sparks flew. This warmed our hands, and was supposed to warm our legs when put into our trouser pockets; a wonder we didn’t set ourselves alight. I remember throwing a stone through the window of an empty house and scampering off home. I arrived home panting, and my Uncle David who would be about sixteen at the time, saying ‘You young devil, what have you been up to now?’ He never found out.

For a halfpenny, we kids could do the Circular Route, a tram ride round the city. We used to sit in the front seat on the top deck, which was open to the sky, and sing the popular songs of the day, which if I remember correctly, were Boer War songs. Kids who are allowed to run wild become precocious, and at six or seven we were well able to take care of ourselves.

My Uncle David was a sport, but Walter the younger brother was a very quiet young man who occasionally had epileptic fits, caused by a fall from a wall onto his head, when he was younger. David had pinups of all the boxers, wrestlers, etc in his bedroom. He taught me all the wrestling holds and had me boxing the other kids in the yard. He had a punching bag hung from the ceiling, and he would fight anybody his weight for a pound. He taught me to swing Indian Clubs, and one day he took me down to the pub, stood me on the table and told me to swing. I went through my repertoire and then he told me to go round with my cap. I got a few pennies but I was ashamed; I felt like I was cadging.

Home again

About this time my father married again and came to Oldham to take me back to Great Harwood. I don’t remember much about my stepmother; I think she was a drunk. I remember seeing her drunk once and it wasn’t a pretty sight. Her mother, who minded us while father and stepmother went to work, was a strict Anabaptist on one side and a moustachioed virago on the other, and tormented us with her restrictions. Can you imagine me, who had been as free as the wind, under such conditions? She would have ruined my sister and me, had the marriage lasted. The marriage didn’t last very long; it was a failure from the beginning. When it finally broke up, my father took us to live with his mother again. My paternal grandmother tamed me with love and affection.

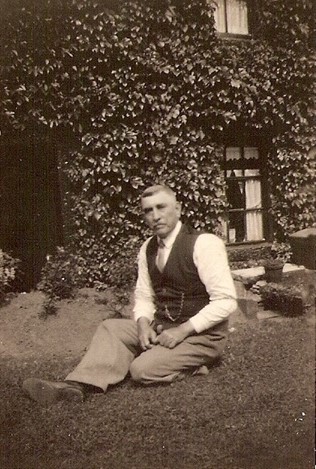

My English grandmother lived in a little stone cottage on the edge of the town. This was a ‘grace and favour’ house belonging to the Church of England. There was a date on the door-jamb: 1828. The walls were eighteen inches thick and we children could sit in the windowsills inside. The doors were massive and the lock was about ten inches by seven inches and the key was six inches long, and must have weighed a quarter of a pound. The lock was supplemented with a big iron bolt. The whole place was covered with ivy, not the common ivy, but a kind my grandmother called ‘Hiven’. The tiny reddish purple leaves would show in spring, these would then develop into green leaves as big as my hand and in autumn would turn to red and gold and fall off, so the house was never damp. I often had the job in summer time, of cutting back the ivy tendrils from around the windows with a pair of scissors. The roof was covered with flagstones an inch thick. The rafters must have been oak beams, and massive, because the roof showed no sign of sagging and we had never had a leak. Under the stairs was the buttery, with flagstone shelves and a bread crock on the floor. Bread was baked once a week and kept nice and fresh in this crock, which would hold a dozen loaves.

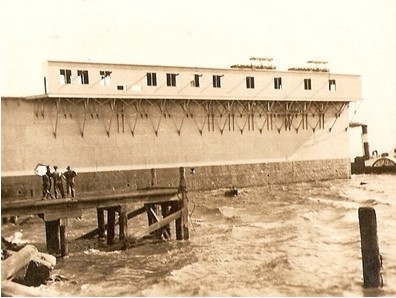

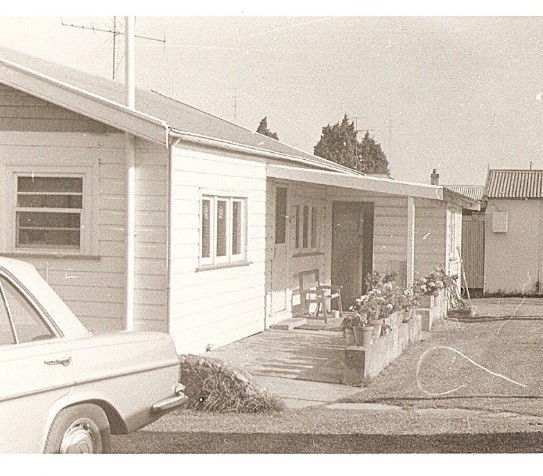

54 Delph Road, Great Harwood.

This shows the ivy that William had to keep trimmed.

Butter and cheese and milk and eggs were kept on the shelves. It was always nice and cool. There was a small leaded light window, the panes of which had been poured, not rolled, and these panes were much thicker in the middle and when you looked through them the outside world was distorted.

I was sent to the nearest school, which happened to be Wesleyan. The schools all seemed to be denominational, subsidised by the government I suppose. I attended for kindergarten and first class. Then my grandmother decided to send me to the Catholic school, which was on the other side of town. I had to go with two little girls, O’Neills I think. We arrived late; they were saying prayers and we had to kneel down just inside the door. When the prayers were finished the Head Mistress came along with a strap and gave us a hiding for being late.

I was allotted to a class, and I think I surprised the teacher by being able to answer all the questions, having had that lesson before, but the belting I had secured at the start still rankled and I decided that that place was no good for me. So, at playtime, I climbed up the lavatory door and over the outside wall and went home. I refused to go to that place anymore and my grandmother gave in and sent me back to the Wesleyans.

We had flag footpaths around the house. One of the flags at the back of the house had a date carved on it, 1606, nicely carved with a border around it. It had probably come from a previous building on the site. We had a sizeable garden back and front, with stone walls around them. The front garden had been so built up over the years that we had to mount two steps to go into it. In the springtime my grandmother would say, ‘Go to the market and get one dozen Canterbury Bells, one dozen Stocks, one dozen Asties and one dozen Sweet Williams’. These were merely to supplement the perennials, which came up every year. There were a lot of bulbs in the ground that came up year after year, crocuses, daffodils and tiger lilies. The crocuses were the early birds and often came up through the snow, purple and yellow and white. The footpaths in the garden were made up of cockleshells, collected on annual holidays at the seaside. I remember one plant much like a succulent; after a shower the rain would gather in dewdrops on the leaves and these dewdrops would glitter in the sun, beautiful. Visitors would ask, ‘What do you call that?’ and grandmother would reply, ‘Mind your own business’, then she would laugh and explain, ‘That is the common name of it. I don’t know the botanical name.

Grandmother used to plant climbing nasturtium seeds at the bottom of the walls and by midsummer the walls were covered. Where the bees came from I don’t know, but the place used to hum. If you came home late at night the bouquet of scents was something to remember.

My grandmother was a great collector of china ornaments. She had a collection of china dogs and horses, all highly glazed. I used to like to stroke them because they were so smooth. She had a set of little brown jugs, brown and gold, and many ornamental plates with landscapes and hunting scenes on them. I remember one piece, a rose bowl with a seat, a cavalier standing and a lady seated, and written in gold letters ‘Come along, these flowers don’t smell very nice’, and when you turned it around there was a little boy squatting with his trousers down. The plates and jugs were never used and reposed on what was known as the pot shelf. Occasionally they were taken down and carefully washed in soapy water until they gleamed in the lamplight.

England is a comparatively cold country and the focal point of the living room was the fireplace. The fireplace had ornamental jambs and a seven-foot over mantel on which was a set of brass candlesticks, six of them. The fireplace was black-leaded; the black lead was put on with a brush and another brush used to polish it. The workday fire irons, i.e. ash pan, fender, tongs and pokers were made of steel and had to be polished with emery paper, but on Friday night brass fire irons were brought out from under the couch for the weekend. The weekday lamp was just a plain glass kerosene lamp, but on Friday evening out came the reading lamp; this had at the base a foot of entwined bronze dragons, a pink bowl for the kerosene, two and a half inch wicks, covered with a plain glass globe and one bigger globe with yellow flowers on it. During the week this lamp reposed on the chiffonier. This chiffonier was grandmother’s pride and joy. It was a set of drawers nine feet wide, made of Honduras Mahogany, highly polished, with brass handles, and we kids were so well trained that we never went within two feet of it, at least not when grandmother was around. This room also had two big rocking chairs and a couch with covers, two ladder-backed rush-bottomed chairs, a table and a homemade hearthrug. All very Victorian, but cosy and homely.

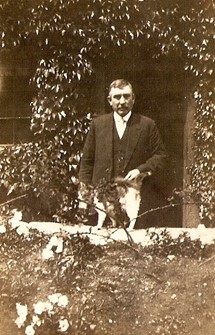

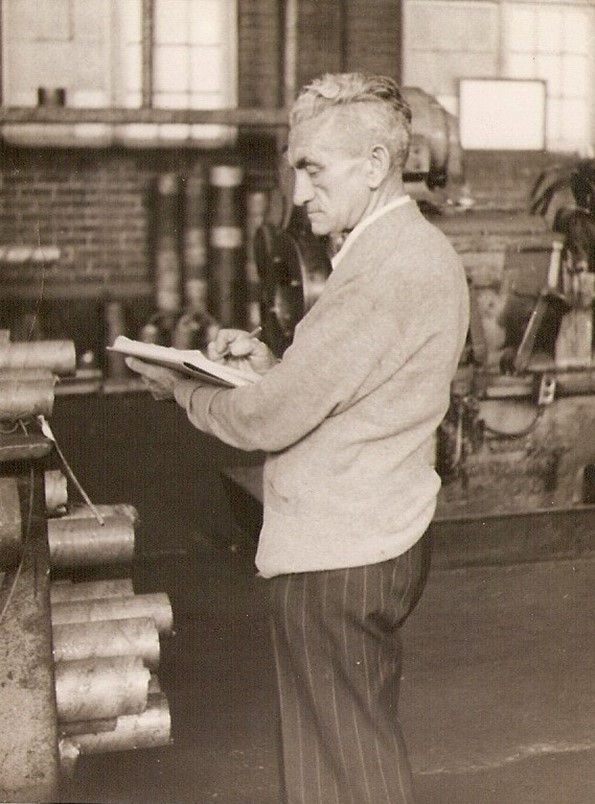

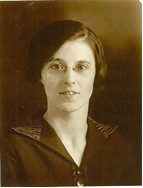

(William’s grandmother.)

Grandmother’s hair was naturally curly but she parted it in the middle and pulled it severely back and wound it into a bun at the nape of her neck.

Great Harwood was a market town, and every Friday night a market was held in the town square. There were about forty stalls selling everything: shoes, cheese, fruit, crockery, chickens and rabbits. A pair of ex-soldiers sold rabbits; they were well known characters named Sandy and Pazza. They always had a crowd around the stall listening to their wit and repartee, ‘Fine fat rabbits, legs like farmer’s daughters, bellies like landlords, sold again and got the money, wrap it up Sandy’. There was often a man with an amusing line of patter selling a cure-all, probably a solution of liquorice and sugar. If it did you no good, it would do you no harm. We kids would buy a halfpenny lucky bag. In the lucky bag would be a small toy (perhaps a monkey on a stick) and a few lollies. Alf Fifty had a marquee and sold hot peas. For one penny you would be provided with a pint mug of black peas and a spoon – very good.

Sandy, Pazza and Fifty were nicknames. Quite a lot of people had nicknames. I remember, ‘Collier Dick’, ‘Celery Joe’, ‘Dick O’Bows’, ‘Dog Arse’, ‘Old Nip Currant’, a storekeeper, and ‘Old Blood’, probably because his working clothes were splashed with red dye as he had worked at the dye works. One man was known as ‘Harry Shit’. He was a gardener and must have used a lot of manure.

My father was known as ‘Medlar’. The story goes that his grandfather had backed a foot runner who was called ‘Medlar’ and had won a lot of money. The nickname was passed down from father to son. I was often addressed as ‘Young Medlar’ by older men. There was a saying they used; ‘Old Medlar and Young Medlar, Old Medlar’s son. Young Medlar will be Old Medlar, when Old Medlar’s done’. These nicknames were so much used that people forgot their proper names. I remember a man coming to our house and enquiring for Mr Medlar.

Great Harwood was a cotton-weaving town with a population of 15,000 and twenty three weaving mills. If you went up the hill (1,700 feet) behind the town during working hours you could hear the place buzzing. And if you were there at knock off time, when all the mills stopped, the town seemed to die and you could almost feel the silence.

Great Harwood was built of stone from the delphs on the hill behind the town. Masoned stone was used for the fronts of the houses and rubble stone for the backs. The footpaths were made of flagstones about five inches thick. Generally there was an extra big one in front of a doorway measuring about eight feet by six feet. The streets were paved; the pavers were masoned and about twelve inches by six inches and six inches deep, they were properly laid on a bed of ashes and the road cambered to the gutters. They then swept stone chips into the nicks and poured in pitch. The paviours were ranked as bricklayers. I think these roads would last forever. The stone was easy to keep clean and every time it rained, which was pretty often, we got a new look.

I must tell you here about the ‘flags’. The hill behind the town was composed of sandstone with only a few feet of overburden. This sandstone must have been laid down millions of years ago. These strata of sand (I should imagine) would be eroded from the cliffs of the land. The strata of sand were interspersed with a thin layer of vegetable silt, probably brought down by rivers in flood. When huge blocks of stone were blown down by explosives, wedges were inserted into the silt layer and the slabs were split off so cleanly that they needed no trimming. These slabs were made into squares or oblongs suitable for whatever was required. The whole town was built from hardwearing sandstone including houses, roads and footpaths. The thinner slabs, say from one inch to four inches were known as flags. One-inch flags were laid like big tiles on the roofs of houses in the early 1800s, but were superseded by slate from the slate quarries in Wales.

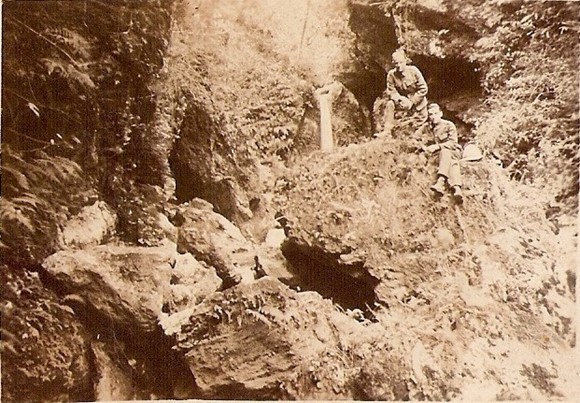

We lived at the top end of the town almost under the hill. As a boy I spent all my spare time on the hill. It was approached by way of the ‘old bent’, a sunken road which had been made by the carts coming from half a dozen delph quarries. The road had been worn down by six to ten feet below the level ground. It was topped by hawthorn hedges, which were a wonderful place of hideouts, bird’s nests, wild strawberries and blackberries. The top of the hill was always windy and on a fine summer’s day great white clouds would be sailing along. There would be as many as half a dozen skylarks singing at once.

There were a few dairy farms on the hill. The cows spent all the winter in the shippons, were hand fed and only let out to drink after being milked.10 They were let out into the fields in summertime, to chew the cud and sit in the sun. The grass was very poor, coarse like buckram.11 The farmers were prosperous because they sold their milk straight to the consumers – no middlemen. They took their milk around in milk floats, two wheeled, gaily-painted carts with shining cans – milk, skimmed milk which we called blue milk, and cream. The farms were very old; two I remember with dates on the door lintel of 1606 and 1609.

We played ‘hop, step and jump’ and ‘stand back-stand in’, between bird nesting and climbing trees. We made collections of birds’ eggs and leaves and caterpillars. We were regular young naturalists. On weekends and holidays we went further afield. Sometimes we walked as much as twenty miles there and back to the famous Stonyhurst College.12 In summer time the Ribble Valley was beautiful. In May all the hawthorn hedges were in bloom.13 From Cronshaw Chair, a high rocky place, it looked as though there had been a snowfall and all the air was scented. No one ever picked hawthorn; it was considered unlucky to take it into the house.

We often raided ‘Old Henry’s’ pear tree. It was about twenty feet high and had never been pruned. The pears were unsaleable, being very small; he probably fed them to the pigs. We used to throw up a stick and then the pears would rain down. We wore knickerbockers, trousers buttoned below the knee, and we filled them up until we could scarcely walk.

We could always tell when Old Henry was coming. He had to come through a small tunnel under the railway where he kept fowls. When the fowls came rushing out, ‘Here he comes!’ He must have been about eighty. He used to shake his stick at us and shout at us, ‘I’ll skin ye young devils alive’. This amused us greatly. I don’t think he really minded. The pears were sweet and we never suffered any ill effects.

In the wintertime we played bowl and hook, with an iron hoop about three feet in diameter, which we pushed along with an iron hook. We got quite expert and could perform complicated manoeuvres with them. When there was snow on the ground we used to knock sledges (pieces of steel about six inches long with two spikes) into our clogs, which had wooden soles. With the snow trodden hard on the footpaths, we would scoot along like ice skaters. The clogs were not like Dutch clogs, but more like a shoe with wooden soles. The leather tops were nailed to the wooden soles with brass tacks. Some of the men’s clogs had pointed toes and patterns cut into the leather – quite flash.

The girls played ring games in the streets, like ‘in and out the windows’, ‘stand and face your lover’, and ‘my fair lady’. After about seven years old the boys no longer played with the girls.

We spoke in broad Lancashire dialect. People from the south of England couldn’t understand us but we seldom saw people from far away. There wasn’t much travel in those days. Boys and girls were ‘lads’ and ‘lassies’. And we used ‘thee’ and ‘thy’, except to our elders; it would be considered cheeky to address anyone older than yourself as ‘thee’. We had to speak what was known as ‘proper’ at school, but lapsed into dialect as soon as we were outside.

I was considered a fair average scholar at school and reached standard six when I was twelve years old. At twelve we started in the mills. I don’t ever remember being asked, ‘What are you going to be when you grow up?’ It was understood that we went into the mill. At first, we were known as half-timers; half a day at the mill and half a day at school. At thirteen we were working full time. We then got two looms next to the person who had taught us to weave. Generally it was the father or mother. In my case it was my father. We worked 56 hours a week, with one week’s holiday a year without pay. In wintertime we went to work in the dark and came home in the dark.

It was now that we got fresh mates, making friends with other youngsters who worked in the same mill. We didn’t have much money. Most of us got pocket money of a penny in the shilling on our wages. A two-loom weaver earned about twelve shillings a week, so we got one-shilling spending money.

The war years

Joining up

It was about this time I joined the Boys’ Brigade. Most of our officers were either Sunday School teachers or St John Ambulance men. We were taught first aid and gymnastics with a talk on how to be good boys in between. We had a very good gym instructor, an ex-army man who could do the ‘flying angel’ on the horizontal bar.14 We used to meet every Thursday night. We had church parades about once a month and an occasional picnic parade to some place that catered for picnic parties. We used to raise our own money by collecting newspapers. We had them by the ton and we sold scent cards, a penny each. One could smell them a mile off.

On our off nights we wandered around the town singing the popular songs of the day, ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, ‘Play a little Ragtime on your Violin’, and ‘Ragtime Cowboy Joe’. We were a pretty harmless lot. The Boys’ Brigade seemed to be a kind of apprenticeship for the St John Ambulance. Quite a lot of the boys joined the St John when they became sixteen or seventeen.

In 1914 when the First World War broke out I was sixteen. Most of our Boys’ Brigade officers and our older mates were called up and went off to Netley Hospital in Southampton, while Alec Chippendale (known as ‘Chip’) and I looked enviously on. We were determined to get in somehow. We joined the St John first aid and sick nursing classes at the St John headquarters in Accrington about three miles away. We walked over there every Wednesday night. We were swotting all the time and we knew the name of every bone in the body, all the pressure points for stopping bleeding and all the antidotes for stopping poisons. We used to recite them as we walked over to the classes. The exams were about six months later. I got to show the treatment of a simple fracture of the forearm and some simple questions, after all that swotting. We got our certificates!

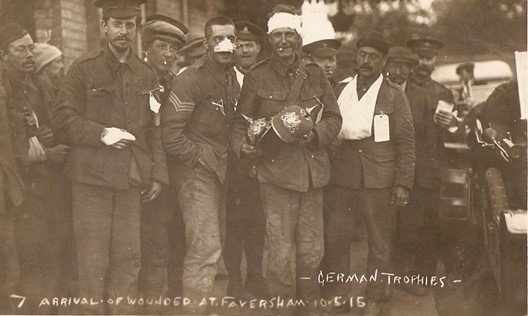

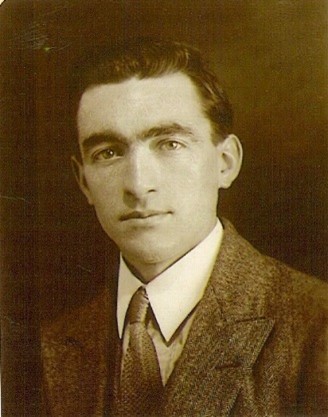

We had told old Doctor Clegg that we intended to join the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He said, ‘How old will you be at the recruiting office?’ We said, ‘Nineteen’. Says he, ‘That’s right’. The old devil! We went to the recruiting office on the 10 April 1915 and after a cursory medical examination we were sworn in. We said, ‘Nineteen’ without batting an eyelid. I had just gone seventeen. We were told to be at a certain place on a certain date not long after. When we got there, there were ten of us and a St John sergeant, who was to retain his rank in the RAMC. We were to proceed to Fort Pitt in Chatham, Kent.

I didn’t join the army from any great patriotic motive but for adventure, and to get out of weaving which I thoroughly hated. So, we proceeded to Chatham, which was quite an adventure to me as I had never been more than 30 miles from my hometown before. We arrived at Chatham in the blackout and we were pulled up every hundred yards with a bayonet under our chins. ‘Halt who goes there?’ and the sergeant had to say his piece. After supper (two thick slices of bread, a tin of salmon between two of us and a big bowl of cocoa) Chip and I slept on the altar steps in the mess room/come church on Sundays. Next morning I was told by some men who worked in the dining hall that the tables had to be scrubbed. I was told to carry out all the tables and forms and scrub them.15 They helped me to carry them out and went off, as I thought, to do some other job and I proceeded to scrub them with soap and scrubbing brush in my nice navy blue suit – my first suit with long pants. I had pretty near finished them when I became a bit suspicious. I peeped into the mess room. The rest of them were playing cards. Oh, the mug recruit!

In a couple of days we were issued with uniforms and I bundled up my soap-stained suit and sent it home. At first the uniforms fitted where they touched but, after a bit of swapping around, I got somewhere near it. There were German prisoners at Fort Pitt, both army and navy. They were probably regulars. The army men looked quite smart in field grey with a thin red stripe down the pants. They were walked around the fort for exercise. Corporal Angus VC was also there (what was left of him).16 He had a patch over one eye, and one leg swinging in his crutches.

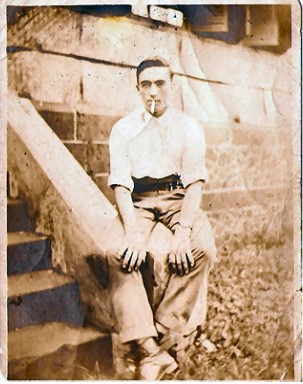

The RAMC insignia is clearly visible on the window in the background. The motto of the RAMC is In Arduis Fidelis and can be translated as ‘Faithful in Adversity’. It sums up the character and the ideals of the soldiers and officers who wear the badge, and is just as applicable in times of peace as it is in war.

Two days later we were on parade. Chip had a sore throat and he had wrapped a silk handkerchief around his neck, it was just showing. All our officers were doctors and when they saw Chip and his silk handkerchief he was sent off to the observation ward. They were scared of Cerebrospinal Meningitis (Spotted Fever), which was a killer in those days and very infectious. So I lost my pal. It wasn’t Spotted Fever.

The rest of us were sent off to Lees Court at Faversham about twenty miles away. Lees Court was a country mansion; they had cleared everything out right down to the parquet floors, except for pictures and clocks. We proceeded to fill it up with beds and hospital gear. There were two doctors, about eight sisters who ranked as captains, about twenty RAMC men and room for about 100 patients. So you can get some idea of the size of the place.

The staff sergeant in charge of us was a martinet. He was a cock sparrow of a man with a tailored uniform and a little waxed moustache. He got my gorge. He didn’t like me either, probably because of my Lancashire accent. He gave me the job of cleaning the bathrooms. I soon became expert and finished the bathrooms by eleven o’clock. I used to lock the last bathroom door, have a bath, sit in a wicker chair, read the paper and admire the Japanese prints on the walls. After lunch I had to clean brasses which, being done regularly, weren’t much trouble. I had to get the milk from the home farm before breakfast. I collected mushrooms on the way back; we often had mushroom with our bacon.

We got our first patients from Neuve Chapelle. They were only slightly wounded, having been cleared out of the French hospitals to get ready for another big attack. I got some ward work then. I remember a young man in the Northampton regiment. He was shot through the cheek and out the other side, playing havoc with his teeth on the way through. He couldn’t talk and looked so forlorn, I felt sorry for him. I used to feed him through a feeding cup with a spout on and generally look after him. When he got his mouth cleaned up he was so grateful and when he got a parcel from his home he lashed me up with cake and chocolates. About the worst case we had was a Lancashire lad with his elbow shattered. The bones on each side of his elbow were in little pieces. The doctor let him smoke while he picked the pieces out. He would never go back to France.

Gallipoli

About the beginning of August 1915, a notice went up on the board wanting volunteers for service abroad. I couldn’t get there fast enough. About fifteen of us marched out one day and I gave the staff sergeant a big smirk as I went by. Please remember I was only a teenager.

We went back to Fort Pitt and I met Chip again and we went out together. We spent most of our shilling a day on food. We used to go to a place and have sausage and mashed potatoes, ‘Two zeps and a cloud’, they knew what we meant.17 We got a really good officer here. He used to take us on route marches and as soon as we got out of town, ‘March easy’ and we sang marching songs. The wags soon had parodies to them. Example of a marching song, sung to the tune of ‘Little Red Wing’:

Oh, the moon shines tonight on Charlie Chaplin, His boots are crackin’, for the want of blackin’, And his little baggy trousers, they want mendin’, Before they send ‘im – to the Dardanelles.

We used to stop in the woods and we would send men out, with a ticket for either a gun shot wound in the leg or shot through the chest. We had to bring them back and show and tell what we had done for them. Really good training. Off we would go again. I think this officer must have lived in Kent because he knew all the nice places. We generally finished up with some ‘ladies aid’ or someone giving us tea and cakes. I remember Cobham and The Leather Bottle pub where Dickens used to drink.

It was a beautiful summer, too good to last. Our officer took us to Aldershot, a real military place. He made us a goodbye speech. He was a good bloke. As soon as he went a corporal took us over and we soon knew we were in the army. This was the place where we learnt to obey without question; right turn, hair cut, every second man, was commonplace, they gave us a ticket and we had to go, even if you had it cut the day before. Some of the men had 00 clippers all over to try and beat this racket.

Chip had been left behind at Fort Pitt and it was at Aldershot that I made a fresh pal, Bill Sykes (shades of Charles Dickens). I referred to him as Old Bill. He was about 28. We slept on the floor in the old married quarters. We never stayed out late, not after nine o’clock. We went home and polished our boots and buttons. We had to be on parade at six o’clock in the morning spick and span. The town was full of military police and if you had as much as a button undone they would march you back to barracks. The punishment was coal fatigue or peeling potatoes for the cooks. We never got caught, we were very careful.

We saw a lot of drafts go out to France from here. One was a regiment of Bantams, little men under normal military height, and they seemed weighed down by their accoutrements. I believe they gave a good account of themselves. A little man is as good as a big man with a rifle, and is a smaller target. The sergeants who drilled us were sarcastic and had a stock of epithets, enough to make your hair curl. One would have thought that we were the scum of the earth. Some of them were quite amusing but we daren’t laugh. So we weren’t sorry when we were drafted.

We got on the train and hadn’t the slightest idea where we were going. We boarded a ship called The Panama late at night in Newport in South Wales. Next morning we were on our way. There was a lot of speculation and rumours but when we kept on due south we knew it wasn’t France.

All the troops sleep in hammocks on troop ships so we had to learn the art of getting into a hammock in confined space, which is not easy. The hammocks were slung on hooks in the low ceilings. Hammocks everywhere, even on the mess decks.

After a reasonable voyage we landed at Malta, an island in the Mediterranean with a long history. We never thought of submarines; we learnt later that there were plenty in the Mediterranean. We went to Floriana and later to a hospital in Valletta high on the shore of the harbour. Most of the streets were steep and were mostly steps. I was put on the wards, floor polishing and scrubbing lockers among other things. This ‘maid of all work’ wasn’t to my liking.

One morning I went on duty at 6am and found that my workmate had been on emergency duty during the night and wouldn’t start until 8am. I was supposed to tidy up the beds, cut bread for about fifty patients and boil eggs for some. I had never known this before, making breakfast on the wards. I don’t know the reason. Being single-handed, I was behind when the sister arrived at eight o’clock and we had a set to. I gave as well as I got but she didn’t report me. I think I got away with a lot on account of my youth.

That same night I was on emergency duty. When I arrived on the ward at midnight, lo and behold, the same sister! She was on emergency duty too. We had a patient with a painful kidney complaint and we were packing him with hot water bottles all night. She was tired like me and was very sarcastic. It was a long, weary night. When I went off duty in the morning, there was a notice on the board, ‘Wanted: Volunteers for Gallipoli’. ‘Come on Bill’, I said to my mate. Bill was a bit reluctant but he came; however he failed to pass the doctor so I lost another mate. We were issued with tropical kit and all packed up and ready to go by 11am. I’d had about two hours sleep in the last thirty six hours. We marched down to the wharf and boarded a ship with hundreds of horses on the deck above us. Stamp, stamp, bang, bang. Stamping horses. This was going to be a wicked trip.

At the very last minute, the RAMC men were called up and we went aboard the hospital ship Kara Para. This was better, plenty of room and better food. We sailed away for Gallipoli, very conscious of submarines this time. The troop ship Royal George had been sunk about a week before. About 100 RAMC men had gone down with the rest of the troops.

We had good weather as we sailed through the Aegean Sea with beautiful islands all around us. It was a pleasure trip. We sailed into Mudros Harbour; the island was called Lemnos, the village was Mudros. We saw four big liners anchored there: the Lusitania, the Mauritania and I think the other two were the Olympic and the Aquitania. I am not sure about the names of the last two but they all had three or four funnels and were the biggest ships of their day.

After a few days we sailed for Suvla Bay. It was 5 November 1915, Guy Fawkes Night. When we got near, we could hear rifle fire and machine gun fire and star shells going up every few minutes. It was a regular Guy Fawkes Night. We landed at Suvla Point and slept in the open on a hillside. Awake at dawn, we heard a shell whistling through the air and all dived into the nearest hole. A rueful laugh as the shell went into the sea a mile away. We soon learned to tell by the sound when they were going to drop near to us.

We were apportioned out to three field ambulances and one casualty clearing station. About ten of us went to the 40th field ambulance that night and slept in the open again, waking up with heavy dew all over us. Next day we dug ourselves a dugout. This is a hole about seven feet square and six feet deep. We threw up the dirt on the enemy’s side and covered the hole with rubber groundsheets, cutting shelves in the sides for our gear, of which we hadn’t much. There were four men to each dugout. I was put in B section, stretcher-bearers, which suited me.

We went up to the trenches every night crossing a dry salt lake. A small stream ran through the lake with a single plank across it for a bridge. This bridge was a bit of a hazard on a dark night, especially for the back man on the stretcher. If we had put anything bigger across, the Turks would have blown it up.

When we came to the foot of the hill there was a tree. Captain Glen would quietly halt us, ‘Two squads sprint by when the next shot goes off’. I think the Turks must have had a rifle mounted on a tripod that lined up on the track and they fired it every few seconds on the off chance of hitting somebody. I think the tree must have been full of bullets but we never stopped to see.

One day we had to go to Lala Baba. Lala Baba and Suvla Point were the two horns of the bay and the only places where one could get real cover; General Headquarters, the mule lines, and stores were there. We had to get a wounded man from General Headquarters down some steps and along a ledge cut into the cliff face. He was facing the wrong way, as we wanted to take him up the steps headfirst so we backed into a cave entrance, which had a blanket for a door, to turn round. A loud cranky voice, ‘Get that man out of here’. It was General Munro. I think he was the man who organised the eventual evacuation and he did a good job.

Another day we were watching a water wagon drawn by four mules, travelling along the beach road. This must have been an emergency as it was very seldom anything moved along that road during the daytime. Sure enough, down came the first shrapnel shell and knocked the driver off his perch. One of our men ran over and crouched behind the cart for the second shot, which knocked out the two leading mules. He cut them out of the harness; we grabbed the shafts and he drove the two mules and the cart to cover. Then we had to go and get the driver (more about this man later).

Most of our patients went straight to the casualty clearing station after first aid. We had a few tents for patients if necessary, but the tents were full of bullet holes and very leaky. The Turks respected the Red Cross so long as we kept quiet. They could have blown us into the sea at any time. We built some ablution benches. They let us finish building them, and then blew them up.

One night I was detailed to the ration party. Away we went to Lala Baba. We drew the rations and loaded them onto small carts, which were drawn by two small mules about the size of a donkey, and started for home. About halfway there the sergeant seemed to think we were on the wrong track. There was what seemed to be shallow water about eight feet across. The sergeant thought that the track was on the other side of the water. He tried to get the Indian driver to pull over but he would not have that. The sergeant then went to the mule’s head and pulled it over. The water was about three feet deep. The sight of the sergeant up to the waist in water and the driver’s explosive outburst in Hindustani were too much for me. I doubled up and laughed till the tears ran down my face. We had to unload the cart before we could get the mules out. The driver was on the right track after all. On 17 November (I remember the date because it was my father’s birthday) we were sitting in the dugout when it started to rain. It rained very hard and then after a while it started to run into the dugout. We stood on ammunition boxes for a while and then we had to get out, as it was filling up rapidly. I tried the patients’ tents but it was pouring in there. I even tried the operating tent but that was a wet, miserable place. At last, I found a tent a little better than the rest and I lay there shivering for the rest of the night. When it came light, I saw that the man next to me was one of my dugout mates. He must have known who I was, because I had spoken to him when I got into the tent the night before. He was rolled up in about seven blankets. He was no longer a mate of mine.

The next day we had a lot of frostbite cases. We wrapped them up and took them to the casualty clearing station, which was across the road and on the beach. They told us that both the Turks and the British had to get out of the trenches and declare a truce until most of the water ran away. Someone must have been bailing out the dugouts while we were on that job. I don’t remember doing any bailing myself.

The next night we had to go to the trenches but we couldn’t go the usual way because the salt lake had risen and covered our track. We had to go around the Lala Baba towards the Australian sector, all of six miles. When we got to the trenches we went into a big dugout. A sergeant major was lying on a cot. His sergeants were persuading him to stay where he was until better weather. He was crippled with rheumatism and it was a bitter, cold night and wet. I was relieved when he decided to stay, as he must have weighed about twenty stone.

The stretchers were soon filled and I got two walking cases. One of them wasn’t too bad, but the other one had his head down and plodding when we started off. After about half a mile the better of the two said he would go ahead with the other party. By this time, my patient was weaving and it wasn’t long before he was staggering. It was like taking home a drunk after a wild Saturday night. He was getting worse all the time and I lost the track.

We kept falling into shallow trenches, which had been dug to fight a rear-guard action if the anticipated evacuation went wrong. These trenches were full of water and we were soon in a mess. He was game and kept going although he never said a word. I don’t know what the matter with him was. I suspected dysentery, as it makes one very weak. He probably had a ticket on him somewhere but it was too dark to see.

After a long struggle we eventually reached Lala Baba and the beach road. Everything was quiet; nobody about except a few sentries so I knew that it was long after midnight. By this time the tails of my great coat were frozen stiff as boards and were chaffing the back of my legs, although I was wearing putties. It was better going slowly, and with frequent rests we got to within a few hundred yards of the 41st field ambulance, where we had been told to take our patients. He got down here and went to sleep. I shook him and pleaded with him. I said, ‘If you go to sleep here you will freeze to death’.

I was just thinking of going to the field ambulance for a stretcher party when along came four ambulance wagons. They were great lumbering things drawn by four horses. I shouted for them to give me a hand. Either they couldn’t hear me or didn’t want to. As the last wagon was approaching I shouted to my patient, ‘Last chance!’ and dragged him up. I got his hand on the back bar of the last wagon, clamped a hand over his and my arm around his waist; he walked a few steps and then dragged. When we got opposite the 41st we both dropped off. We took the last few yards to a lighted tent with a rush and almost fell into the tent. An officer said, ‘Which is the patient?’ I gave a sickly grin and dived out of the tent. When I got back to the 40th my mates had a fire going and some bacon sizzling in the pan. In half an hour I was as good as ever. Youth quickly recovers.

It was a queer sort of life; we were always on duty. We learned to eat when we were hungry and to sleep in snatches. When we awoke we were alert immediately, like the animals. We did most of our own cooking. We were issued with biscuits, bully beef, bacon, tinned cheese, and tinned butter. The tinned butter was awful and we couldn’t eat it. All that the cooks made was bully beef stew and tea.18 We slept in our clothes and we were lousy. The lice were no respecters of persons, the officers were lousy too.19 There was always something happening, but I only remember the outstanding incidents.

The Gallipoli campaign had developed into a stalemate, the troops told us that there was so much barbed wire in between the trenches that neither side could attack. If they blew it up, it fell down again in a more tangled mass than ever. The Turks had the advantage of the hilltop positions and all their lines of communication were behind the hill, out of sight. We had no aeroplanes to spot for the artillery.

The navy came into the bay occasionally and bombarded the top of the hill. But it seemed half hearted and they never stayed long. I think they were frightened of submarines; several navy ships had been torpedoed. Kitchener came some time during December and said, ‘Get out’.20 This was easier said than done. If we could get off without casualties it would be a major triumph in itself. The evacuation was very well planned. A quarter of each unit were to get away each night. Towards the end there were very few of us left. We were encouraged to walk about and show ourselves so that everything would look normal to the Turks.

The last day we spent destroying everything. I myself hoed into a tea chest, a yard square, and scattered the tea in the sand. We cut every sand bag and slashed the tents to ribbons on the side away from the enemy. We weren’t allowed to take anything away, not even a tin of milk.

That night we paraded after dark. No smoking, no talking, no tins to rattle. We met the troops and fell in behind them. The ambulance always brought up the rear. It was remarkable how so many troops could move with so little noise.21 We could relax a little when we got to Suvla Point, and as we were too far away from the Turks for them to hear us I remember a naval petty officer shouting in a loud voice, ‘Are there any more for the Princess Ena?’ We were marched straight into a landing barge four abreast. When it was full, the hatch clanged down and we were taken out to a ship in the bay. I don’t remember anything about the ship as everything was blacked out.

The engineers were the last away. They rigged up many gadgets to deceive the Turks. One of the ideas was a fixed rifle and two tins. The top tin dripped water into the bottom tin, which had a string connected to the trigger of the rifle. The drips were regulated so that the rifles could fire at intervals. This gadget can be seen in the war museum in Canberra. The engineers then poured rum, petrol and kerosene over the stores, which were as long and as high as a row of houses, and set them alight. That was the end of the Suvla Bay.

Cape Helles on the tip of the peninsula was evacuated a week later under the protection of the Navy. We went to Mudros in Lemnos, the island that had been the base for Gallipoli.

One day we went to the other side of the island for a swim, I was playing about up to my neck when suddenly I went down, down, down. I was no swimmer and had a bit of a struggle to get back to my depth. It seemed they had been dredging for another harbour and I had slipped into the deep.

We could buy figs and oranges here, so we got a few vitamins at last. Christmas was spent on Lemnos and there were a few extra rations and a concert. We had a sergeant who was in charge of the water supply. He was called Waters and he sang a song called ‘The Village Pump’:

And to celebrate the day, in a proper kind of way, we put another handle on the wpump, the village pump.

The Middle East

We boarded a big ship in the harbour about New Year’s Day. I forget the name of the ship. We sailed on a dark, stormy night, very conscious of the submarines this time. Some of the men were playing cards and some of us were in our hammocks when crash, bang and a rending of timber. Somebody shouted, ‘Torpedoes!’ There was mad rush for the stairs which were soon jammed full. I grabbed my life belt and made for the ladder leading up to the open hatch. Somebody shouted, ‘All right, all right’. Things calmed down a bit. It seemed that a deckhouse had broken loose and crashed into a donkey engine. We got quite a thrill.

I had had enough sleep and went up top for a breath of fresh air. I was sheltered under the lee of the bridge when a young officer on watch on the bridge started to sing in a soft voice. Can you imagine being on a blacked out ship, the swish of the sea and the moan of the wind and a soft voice singing? I learned the song later, but have forgotten the words since. It went something like this:

Little white hands from the window waving, Dear brown eyes so bright and gay, All is done the sorrow and craving, Donald is coming to you tonight my dear, Sweet, sweet, heart oh my dear, There is never a sea can bar my way, Night or day, night or da-ay, There is never a sea can bar my way.

We arrived at Alexandria in Egypt the next day and then went on to Port Said where we disembarked. We pitched camp on a piece of spare ground near the entrance to the canal, with a mosque overlooking us, and we weren’t very far from the sea. We spent most of our time in the sea. It was a beautiful beach and the weather in Egypt in January is ideal. We had about a fortnight here and it was here I developed a craving for sweetened condensed milk. I had quite a few tins.

The native quarters were out of bounds to us; we were only allowed along the main street and on the waterfront. I was going down the main street one day when a civilian Frenchmen stopped me. He had no English and the extent of my French was, ‘Oui oui’. I tried to tell him that I was going to meet a friend who spoke French fluently, but I could not make any headway. I don’t know what we missed. He didn’t know what he had missed either; we hadn’t got rid of the lice yet!

We travelled down the canal on the railway that runs alongside the canal more or less to Port Suez. We travelled in open goods wagons and the wags made it a party, chiacking the camel drivers and canal workers.22 There are always a few clowns in a crowd of young men. They had picked up a lamb on Mudros and it turned out to be a ram and was christened Charlie Chaplin after the great comedian.

When we arrived at Port Suez we embarked on the troop ship Ionic, a ship of about 20,000 tons, I guess. We sailed down the Red Sea and up the Persian Gulf. It was hot, so they rigged up a tarpaulin and filled it with water. We were allowed only about ten minutes in this tent at a time. When our ten minutes was up, the man who had saved the water wagon on Gallipoli refused to get out and the sergeant reported him for disobeying an order. This was a serious matter for discipline as we were on active service.

When we arrived off Kuwait we transferred to a smaller ship, as the Ionic was too big to go up the Shat-el-Arab to Basra. Basra was a poor old place in those days. No wharves; the ship anchored in the stream, a few barges were moored alongside and then planks laid down to the sloping banks. We pitched a camp about a mile from the river.

The next day there was a court martial, and the man who had disobeyed an order was sentenced to four years detention. He started to serve the sentence in the guard tent and had to do odd jobs, which were more or less what we were doing.

It was here I saw the first case of malaria. A man called Rig who had been in the border regiment at the landing on Gallipoli, and had been wounded and was slightly disabled, had been transferred to the RAMC. He started to sweat, and had a terrific headache, the sweat just poured out of him. After about half an hour he started to shiver, we piled blankets on him and he made the whole lot shake. He had been a seaman and had had malaria before.

We had about two weeks at Basra and then we boarded a river steamer, which was a paddle steamer with a barge tied to each side. I think we went about 400 miles up the river Tigris. One day the rebel, whose detention had been forgotten, had put himself in charge of Charlie Chaplin. By this time he had a collar and a lead and was jumping from the steamer to the barge. The lead was short and Charlie didn’t get a chance to jump. He was dragged into the water between the steamer and the barge. A good job it was behind the paddles, so Charlie went swimming down the river and around the bend, and that was the last we saw of Charlie. Some Arab would get a good dinner.

We disembarked at a place called Sheikh Sa’ad and here we pitched camp. The sergeant had us march to extended order; twenty paces apart, right turn, knock in a peg every twenty paces, eight men to a tent, march to a peg, place the tent pole through the top hole and stand it upright, grab the four red guide ropes and peg them out, then peg all the other ropes out, and dig a trench round the tent, and lead it into the main trench down the middle of the tent rows, and then all hands to pitch two big marquees. In twenty minutes we looked like we had been there a week. The brigadier came over and congratulated us on our smart work.

Sheikh Sa’ad was about eighteen miles from the front and we were there about two weeks. Arab camel drovers used to feed their camels around the camps. There was very little feed, mostly prickly bushes and something that looked like Paddy’s Lucerne.23 The camels would take the stem of the bush into the side of their mouths and with a sideways pull would strip all the leaves off the plant. I think the camel drovers were spies and probably went round our flanks at night and told the Turks what was going on behind our lines. One night we were awakened by a pistol shot, the Captain Quartermaster was chasing an Arab who had crept into his tent. The Arabs were keen on firearms and would go to any lengths to get them. The infantrymen had to sleep with rifle slings over their shoulders in spite of the guards marching around the camp all night. The guards had to shoot on sight. If you had to go to the toilet at night you had to wake the next man to go with you and to warn the guards. An Indian was shot accidentally – he didn’t answer quickly enough.

About the end of March or the beginning of April 1916, we struck camp and assembled after dark; the whole brigade, which was four regiments of infantry, some artillery, transport, signals, and the medical bringing up the rear. We had two outriders with lanterns and we had to march between the lights. Soon after we started out, it began to rain. It rained hard all night with lightning and thunder. We had sixteen miles to go and, being at the rear, we were soon up to the ankles in mud. No overcoats, so it was soon running down our necks. We put our towels around our shoulders and wrung them out occasionally. At dawn we didn’t seem to have arrived at anywhere. We stood and walked about all day. It was still raining. That night we started off again. We were supposed to be looking for a camp and we got lost.

Our officers, who were on horses and had big capes on, halted us to have a confab. By this time we were thoroughly fed up; there were mutterings and growlings and shouts of, ‘Get a move on’. The sergeant was running up and down the lines saying, ‘Who said that?’ Eventually a man rode up and guided us to some tents. They had been pitched on the mud and we had to put our boots under the stretcher feet to keep them out of the mud.

In the morning the sun came out and we dried out clothes on the tent ropes and soon forgot all about it. Next night the bearer section went up to the trenches. We got into a trench and we had a lecture; there was to be an artillery barrage at dawn. We were to follow the troops over when they charged. Named communication trenches were reserved for stretcher-bearers and we had to hand over our wounded to the Ghurkhas. This Ghurkha regiment had been badly cut up somewhere and the remnants were detailed to assist us.

Came the dawn, came the bombardment. We heard the troops shouting and cheering, so over we went. We met some Turkish prisoners coming back with their hands up and soon we were picking up wounded. Every soldier carries a First Field Dressing sewn into the skirt of his tunic. Sometimes the slightly wounded had put their own dressing on and sometimes the regimental doctor had fixed them up. Sometimes we had to fix them up but we carried only shell dressings, a bigger pad and bandage for large wounds. We were soon past the last line of Turkish trenches and out on the plain. The troops advanced six miles that day. Goodness knows how far we walked back and forward all that day and most of the next night, stopping for a rest and a catnap whenever we could.

In training we had four men to a stretcher. Three on one side of the stretcher, one on the other. Three men lift the wounded man, odd man puts the stretcher under him then they lower it gently. All this went by the board; often the wounded man would scramble onto the stretcher himself.

Wounds are not painful in hot blood; it’s when they get stiff and cold that they become painful. We carried no splints. If limbs were broken, we straightened them out on the stretcher. The main thing was to get them out of danger and get them to the field ambulance as quickly as possible, and that’s the way the troops wanted it. They knew if they could get away safely they were out of it for a while at least.

One day I picked up a Turkish rifle. Captain Glen was ordering me to put it down when he noticed it was a Turkish rifle, so he had a good look at it himself. British rifles had mahogany butts and blued barrel and fitting. The Turkish rifle had a very light coloured wood in the butt and bright fittings with Turkish figuring on the back sight.

We were now at Sanna-i-Yat. One morning I was awakened by some men who were killing a snake and then we noticed that the water was rising fast in some low-lying ground. There was a battery of artillery there and soon the water was up to the guns. The horses came galloping up and by the time they were harnessed to the guns and ready to go the horses were up to the belly in the water. We received orders to get to the other side of the river. We had to march back a couple of miles to a pontoon bridge. We learned later that the Turks had blown up the riverbank and let the water into an old dried up swamp. When we got to the bridge we had to break step so that we wouldn’t swing the bridge. There was a big G S wagon in front of us.24 Something must have startled the horses, they started to rear and plunge and soon the whole lot, horses and wagon and all, were in the water. The driver managed to jump clear. All we could see were four horses’ heads going down the river.

We marched up to the front on the other side of the river (Es-Sinn) and soon were collecting wounded. When we were sitting on the side of a trench, waiting for a regimental doctor to bandage a wounded man, I was hit by a bullet. It was quite a blow and I quickly jumped into the bottom of the trench feeling inside my tunic, but no blood. When I looked down, I saw that the bullet had torn the bottom of my breast pocket and through my pay book and my soldier’s small book. When I pulled out the books, the young doctor said, ‘Quite a souvenir’. He grinned and gave me a cigarette.

It was here we saw a sight that would never be seen again, horse artillery galloping into action. The drivers were standing in the stirrups flogging the horses, which were flat out and foaming at the mouth. When they came opposite us they wheeled in unison and unlimbered and spaded in. The horses and limbers galloped off for more ammunition. I noticed that one of the horses had had its leg over the trace and the place where it had been rubbing was blood raw.

They put up a ladder (only one pole with the rungs sticking out on each side) and soon an officer was on top shouting out ranges. I believe they created havoc among the Turks, as it was point blank range just across the river. A German general, who was in charge of the Turks at Sanna-i-Yat, was reported to have said that he could hold it against a whole army.

The Turkish trenches were in the form of a ‘V’, so that an attacking force would be enfiladed from two sides. But, when we crossed the river, our artillery was able to enfilade him from Es Sinn. Rumour had it that our artillery killed 90,000 Turks, and the Turks asked for an armistice to bury their dead. All this was troops talk, but I suppose it could’ve filtered down from general headquarters and was probably true. So the German general was ‘hoist on his own petard’.25

The whole of this business was for the relief of Kut-el-Amara. General Townsend had outdistanced his communications and he and his army were besieged in Kut. We were now about twelve miles from Kut and they said they could see the flag flying on Kut, with binoculars I suppose, and another big attack was ordered. The private soldier knows very little of what is going on except in his own particular sector, but we learned later that the troops had to crawl out during the night and get as near to the Turks as possible. Whispered orders, ‘left incline’, ‘right incline’, until they didn’t know whether they were facing the Turks or not. The Turks must have heard them and sent up star shells. Some shouting, ‘Charge’, some said, ‘Get down’ and some said, ‘Retire’– what a muck up!

When we got up there in the morning, they were all mixed up like a dog’s breakfast and we couldn’t find our own brigade. We got amongst the Lancashire brigade. I saw a man in the East Lancs from my hometown Great Harwood and inquired for Herbert Taylor who lived near me. He didn’t know anything about him. I learned later that Herbert had been killed.

Later in the day Captain Glen called for volunteers and we all stepped forward. We got a Red Cross flag, about a yard square on a pole, and climbed over the parapet after Captain Glen. I think the flag must have been blowing away from the Turks so that they couldn’t see it. Anyway, they kept on firing. A young officer who was wounded in the leg and had been out in the hot sun all day started to scramble towards us. As he did so, he was hit again. We bundled him onto the stretcher and ran for the nearest hole. He must’ve had his arm close to his side when he was hit for the second time. The bullet had ripped along his ribs and inside of his arm. Corporal Eddows bandaged him up and I gave him a drink. We took him to the field ambulance. He was telling us how glad he was to get away as he had had quite enough.

At this time it was very hot weather and we couldn’t get enough to drink. We were only allowed one bottle a day, about a quart. The water came from the river and was filtered through a pair of drill trousers tied at the bottom. Soon the trouser legs were full of sand and then the water was tinted with ‘Pot-Per-Mang’ – Condy’s Crystals to you.26 It tasted like nobody’s business.

We wore helmets and a spine pad (a quilted pad which tied round the helmet by two tapes and hung down the back to protect the spine) and, of course, shorts. We were burned black and for years after my knees were a darker shade than the rest of my legs. We had no thermometers but I guess the temperature was well over 100 degrees in the shade – but there was no shade. You can imagine what it was like in the sun. Of course, there was no water for washing. Occasionally we managed a drop for shaving and after the shave we washed the rest of our faces with the lather brush. Our clothes and towels and handkerchiefs would have broken a washerwoman’s heart. I did get one bath in Mesopotamia. The Turks must have blown up the riverbank (an old trick of theirs) and the water came rushing down an old trench. There were shouts of glee as we stripped off and jumped into this muddy mess but the officer soon had us out of it and then we realised that the water must have been horribly polluted. Dead horses were often seen floating down the river and they were like big black balloons, and the black was flies.

One day, when we were back from the lines, we had to dig a hole on the riverbank, eight foot square and eight foot deep. We draped a tarpaulin in this and pegged down the sides and proceeded to pump this full of water from the river. An old fashioned pump with a long handle on each side, two men on each handle, up and down, up and down. We had almost filled this when an officer came along and saw a dead sheep, which had drifted to the bank a few yards upstream. He made us pump the whole thing out and start again after we had pushed the sheep off into the stream.

Our kit consisted of haversack, water bottle and mess tin. In the haversack we had towel and soap, knife, fork and spoon, a small writing pad and pencil. On our belts hung a jack-knife with blade and spike and tin opener which we used for opening bully beef and jam tins. We had a stretcher sling that went under our epaulets and round our shoulders. The ends of the slings had loops, which went on to the handles of the stretcher so that we carried most of the weight on our shoulders. When not in use, we tied the ends of the sling behind our backs and of course the ever present one stretcher to two men – eight pounds.

If we had a place to come back to, we left our haversacks and mess tins behind. We were all lean and tough as pin wire and even I could carry the heavy end (head end) of the stretcher at a jog trot for half a mile (more or less), according to the weight of the patient. One day we were told to go and get the colonel of the Warwicks. We received directions and away we went. We passed a lot of wounded on the way, who were calling for stretcher-bearers. I suppose they would tell later how the stretcher-bearers had ignored them. When we found the colonel his batman was looking after him. He was shot through the head and was unconscious. When we got him to Captain Glen, he shook his head and said, ‘Take him to the field ambulance’. We told the Captain about the wounded and he sent bearers over there.

Later, the Turks did a lot of shelling behind the lines. We saw a mule galloping along with its hoof blown off, probably wounded in other places too. It soon toppled over and Captain Glen shot it through the head with his revolver. Then they got the range of two ammunition barges anchored on the river. They straddled them and then scored a direct hit, a big bang, not much of a flash, but a lot of billowing smoke, and the barges were no more.

There was a lot of shelling about this time, and a lot of casualties. We were working for three days and nights with scarcely any rest. On the last night, I was worn out and I had drunk all my water. My throat was so dry I could hardly talk so I took a drink out of the river. This was a foolish thing to do, and I used to think that this drink was the cause of all my sickness later on. But, when I think of the conditions we lived under, sickness was inevitable. We lived on bully beef and biscuits, with an occasional tin of jam. There were no cooks with the bearer section. We also had what were known as iron rations. These were small flour and water biscuits. We were not supposed to eat these until we had been without food for twenty four hours but we used to nibble at them all the time. Also in the little bag were two OXO cubes and a few tea cubes.27 There was no wood to be had, so we had to boil the Billy with cordite. We did this by tapping a bullet on our boot heels until the bullet was loose and then throwing the cordite under the Billy. It was a constant job as the cordite burnt very quickly.

And the flies; there were countless millions of them. You needed one hand to put the food into your mouth and one to try and keep the flies off. I only remember having one piece of fruit in the eight months I was in Mesopotamia. That was an orange given to me by a sailor on one of the river gunboats. Mesopotamia, now known as Iraq, is a great date growing place, but all the dates I ever saw were hard and green. If you were eating on a windy day, you could feel the sand gritting in your teeth. We were lucky compared with the poor devils in Kut. They had no food at all. They had eaten their horses long ago and were starving. Our army tried to drop food to them from the two airplanes they had, but this was only a drop in the bucket. The airplanes were two small monoplanes and were spotters for the artillery. They were so small you could have run them into a double garage.

So Kut capitulated. The Turks arranged an exchange of British sick and wounded for Turkish prisoners. It’s strange what tricks memory plays. I remember distinctly carrying (piggyback) some of the emaciated men from Kut, but from where to where I have no recollection at all. These were regular-army troops, fine men. They were reduced to skin and bone and I had no trouble at all carrying them, except that I was scared they might fall to pieces if I wasn’t careful.

It was soon after this that I reported sick. I was running a temperature and aching all over and utterly weary. They sent me to an Indian field ambulance. An orderly took my temperature, rushed out of the tent and came back with a doctor. He said I was 106 degrees. I don’t know if he had misread the thermometer or had it in the sun, but I didn’t feel so bad. Later, I went to an Indian field hospital, and it was here that dysentery started. I had had Baghdad Boils (tropical ulcers) all over my arms and legs for some time, but these were ignored. A young Eurasian doctor took pity on me; he gave me lead and opium pills. I had to go to his tent after dark to get them; they must have been in very short supply. These pills improved me enough so that I could crawl down to the bank of the Tigris and get on a barge full of sick and wounded and go down the river. It was a long journey. There were a lot of dysentery cases on board and the sanitary arrangements were awful.

The river was in flood, but there hadn’t been much rain where we were so it must have come down from the source in the Caucasus Mountains. The river had overflowed its banks and some Arab families were marooned on mounds surrounded by water. Eventually we reached Basra and were sent to what was supposed to be a convalescent camp where they fed us bully beef and biscuits. The conditions here were so bad that I begged the doctor to send me back to my unit. He pulled my eyelids down and said, ‘Boy you haven’t a drop of blood in your body.’ He let me go in any case – but not to my unit. They sent me to a kind of outpatients place. There was a doctor, a small man about my size, (five foot three and half inches) and he worked a twelve-hour day with about half a dozen RAMC men, including two from my own unit.

There were hundreds reporting sick every day. Some were carried in on stretchers and they were heat stroke cases mostly. I used to throw water over them, or, if we could get ice, which wasn’t very often, rub them down with a piece. I remember one case who was unconscious and in danger of choking. I had forceps and cotton wool swabs and was dragging out yards of phlegm. I got him down to 100 degrees and he went off to hospital.

After about two weeks here, the dysentery started again, and I got weaker and thinner until I was just crawling around. One day the doctor gave me a list of patients’ names and numbers for the hospital and said, ‘Your name is on that too, and don’t come back’. I remember getting on a bed in my dirty clothes and going to sleep. Next morning the doctor came round, looked at me, and wrote ‘India’ across my sheet. I think I must have been semi-conscious for a time. I remember a man shaking me and saying, ‘You’ve missed one boat, don’t miss this one’. I grabbed my haversack and managed to get onto the ship The Elephanta.

This ship was going back to India empty – so empty that she was top heavy and rolled like a drunken sailor. It was too hot to go below, so we slept on the hatch covers. It rolled so much that we had to hold onto something or we would have finished up in the scuppers.28 There were some empty horse stalls on deck that had been cleaned out. They had dividing rails about four feet high and a dividing eight-inch plank on the edge of the deck. Some of the men were sleeping in these stalls and one night we were awoken by cries and shouts. Planks, which had been stacked on the dividing rails, had crashed down on the men sleeping below. We rushed to the rescue. The dividing planks on the deck had saved them from being badly crushed. Only one man had a broken ankle. We had a burial at sea. I had seen several burials at sea; they sewed the body in a canvas shroud and weighted it with iron bars, then they put it on a stretcher and covered it with the Union Jack, the ship’s engines would be stopped and, after a short service, the body was slipped into sea.

We were now well away from the war and looking back I thought that I had only been at the fighting front for about two and a half months. But two and a half months is a long time when somebody is trying to shoot you all the time.

India

We landed at Bombay 29 and boarded a train for Poona.30 I bought a hand of bananas on Bombay station (ten or twelve bananas) and ate the lot at one sitting. It was the monsoon season and the way over the Ghats (mountains) was beautiful. We dived through tunnels and rushed across bridges over precipitous gorges, and there were waterfalls everywhere.

We arrived at Poona and paraded outside the station. I had on a helmet without puggaree, a dirty grey shirt, a pair of shorts which had been cut down from a pair of slacks and sewn with black thread, no putties, grey socks and my boots were bleached white by sun and sand.31 I had scabby ulcers all over my arms and legs and was as yellow as a canary. I had Yellow Jaundice and I weighed about six stone. A woman passing by said, ‘Oh, look at that boy’. Her husband said, ‘Come along; they’ve only come down for a rest’. I didn’t resent this and I was amused.

They took us to a hall and gave us tea and cakes, but a handful of fruit would have done us more good. We went to the Deccan British War Hospital in private cars. This hospital had been an agricultural college and there was cultivation all around us.

I had trouble sleeping in a bed as I hadn’t slept in a proper bed in about eighteen months. I felt smothered so I went onto the veranda and curled up in a wicker chair. The night sister came along and rooted me out back to bed. I tossed and turned and finally got out onto the floor and slept like a top. I got into trouble over this and had to get used to the bed.