Great Harwood Parish – Overseers of the Poor Accounts

Includes Constables Accounts

Lancashire Archive PR 153

[See the end of the page for links to transcriptions of the accounts]

The poor law accounts for Great Harwood between the years 1732 and 1821 provide a unique glimpse of the lives of the people of the town in the eighteenth century. At that time Great Harwood was a small market town with a dual economy of agriculture and textiles, where the family small holding was supplemented by weaving. It was a town on the verge of industrialisation, the population was growing and there was pressure on land and resources.

The administration of the poor law in England is a complex subject beyond the scope of this introduction. The records were created under the Old Poor Law, which put the task of the relief and management of the poor on the parish. Rates were levied on the inhabitants of a parish, overseers of the poor appointed to assess claims and provide relief, which was, until the New Poor Law of 1834, mostly ‘out’ relief, that is payments of money, goods and services to alleviate need. In 1834, with the advent of the New Poor Law, the workhouse largely replaced out relief. If you wish to know more there are many articles, books and websites about the poor law in England. This is a very good website about the workhouse and the poor law https://www.workhouses.org.uk/

Great Harwood was a manor of two parts, the Lower and Higher Towns, and accounts were submitted by each part of the manor. Accounts for every year have not survived and for some years only the records for one part of the town. The spelling in the transcriptions is the spelling given in the documents and at times it is hard to read; not only is it often spelt phonetically, it is clear it is also the phonetic spelling of the local dialect. Notes in square brackets indicate the intended word as it would now be spelt. Some years have the Constable Accounts listed; these list items such as the militia list, the assessing of land and window taxes, warrants for vagrants, items relating to the highways, and the repair of the stocks.

Applicants for relief had to prove they had legal settlement in the place from which they were claiming relief, and, as these records show, that was often at some distance from where they were living, places mentioned in the records include Padiham, Colne, Blackburn, Preston, Manchester, Liverpool, Warrington and Crackpot in Swaledale. Certificates of settlement were issued to anyone wishing to move between parishes if they were judged likely to become a burden on the parish, and removal orders made when people were found not to have a legal settlement. It was the duty of the overseer to search out the facts and carry out the orders. Transcriptions of surviving settlement certificates can be seen here. The creation of a removal order didn’t always result in a removal, or at least a permanent one; Robert Calvert and family were subject to a removal from Haslingden in 1758, but parish registers show the family in Haslingden for many years after that year.

Who were the poor of the parish of Great Harwood in these years? The accounts show that they were the sick, the infirm, the elderly, widows, orphans and women with illegitimate children, and those children too. Falling into poverty was most common for young families and in old age, and women with children born outside marriage were also vulnerable and there are many instances listed in these accounts where the father of a child is being sought so that he, rather than the parish, will pay for the upkeep of the child. Some people relied on poor relief for a large part of their lives, it isn’t clear why from the records, and no overt judgement or censure appear in these documents.

Relief took many forms; house rent and lodging costs were paid, food and ale were provided, coal for cooking and warmth, blankets, and chaff beds which were mattresses made of straw, clogs and very occasionally shoes – Mary Barret in 1754 had her shoes heeled. The textiles mentioned when material was provided for clothing include: Frieze, drab, lin, blew cloth, brown Lincy for a gown, canvas, flannel, and broad cloth.

When someone died a coffin would be paid for and church fees, and sometimes bread and ale at the funeral. When John Haworth died in 1760 five shillings was paid at Cock for ale and another four pence in Harwood.

If people seemed as if they might become a long term drain on parish resources the means to make a living were sometimes provided. For younger people and children this was often an apprenticeship, when the accounts mention ‘binding’ people it refers to being bound as an apprentice. The expense of this was considered good value if it provided a child with the opportunity to make their own way in the world. For older people tools were sometimes given and in 1785 James Rushton, who had featured heavily in the accounts prior to this date, was given work tools, the parts for a loom as well as food, clogs, a blanket and ‘ofar od stoof’. In 1787 he received shuttles and bobbins, a chaff bed and blankets. Later the same month ‘a jenny’, and in 1789 he was provided with a loom by a Nicholas Read.

An example of an early spinning jenny – this is one from Helmshore Textile Museum.

Photo writer’s own, taken courtesy of the museum.

An example of an early handloom, from Helmshore Textile Museum.

Photo writer’s own, courtesy of the museum.

When Daniel Calvert of Livesey was provided with looms in 1789 the place were they were obtained from was given as Moulding Water, which was and is just to the west of Feniscowles. Daniel had been receiving relief since 1777 so the provision of work eqipment must have been seen as the answer to the problem, however payments continued to be made to him for some years after.

People were cared for in their sickness with many mentions of people being ‘badly’ or having a fever. Several doctors are mentioned, Dr Turner, Dr Talbot, Dr Paicherd but most often a Doctor Sale, who lived in Whalley and who was described at times as either an apothecary or a surgeon. Interestingly, after his death his wife appeared to carry on the business, ‘Paid to Eliz Sale for Doctoring see a bill’ being entered in the year 1794, eighty years before women were officially allowed to practice medicine.

Medicine was often simply wine or ale, but in 1760 Thomas Rishton was given a Daffys Bottle. Daffy’s Elixir was a patent medicine made from various herbs and alcohol, and was a ‘cure all’. The same year a bottle of Eatons Styptick for James Rishton was paid for, and which was a patented medicine to stop bleeding.

When relationships of the people in need of relief and those receiving it are examined it becomes clear that the extended family were in receipt of relief for providing care. In 1759 Robert Birtwistle was in receipt of relief for ‘Daniel child’. Daniel Calvert’s wife had died the previous year and it was clear Daniel was struggling as he claims support many times. Robert Birtwistle was married to his wife’s sister – so the family were taking on the child, but with help from the parish. (This Daniel was an earlier individual than the Daniel from Livesey.)

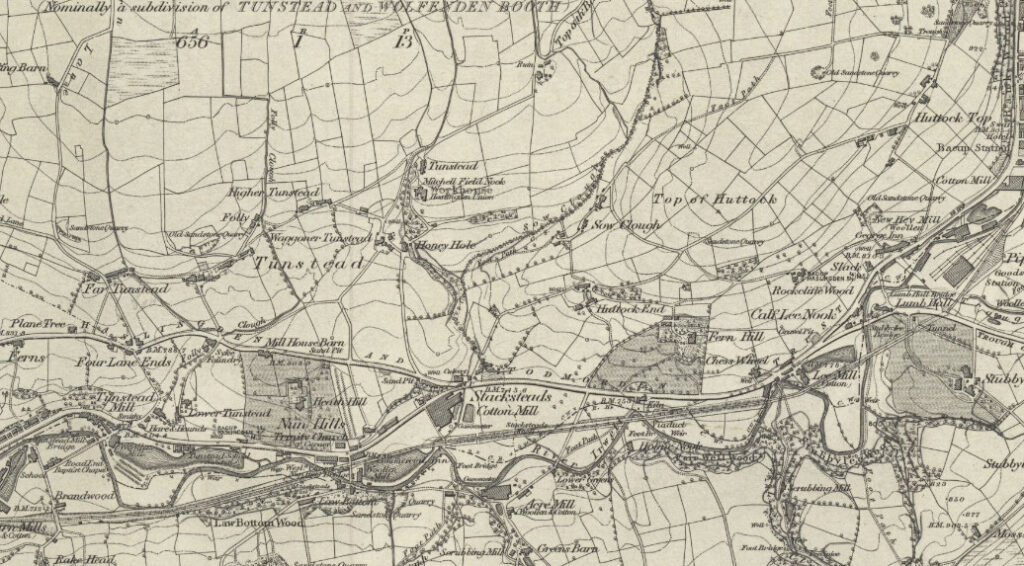

The accounts show that if a person was entitled to relief then all efforts to maintain people in their community were made, but there are instances where people were sent to a workhouse. The first mention is for a payment to Brindle workhouse in 1739, but without a reason for the payment. The next mention of a workhouse is some years later in 1784 and was the workhouse at Rossendale, probably the one located at Tunstead. Maintenance was paid for Francis Clayton and Betty Shuttleworth at the workhouse, and are both mentioned many times in the accounts after this. Both had family who may have been able to care for infirm relatives, so it is a mystery as to why these individuals were sent to the workhouse, perhaps there were health issues, physical or mental, that could not be dealt with in their home.

Sometimes marriages were arranged, which would make a woman who had been claiming parish relief now the responsibility of her new husband, or which might provide a wife for a widower with children in need of care. In these records though, there is an instance of an attempt to stop a marriage, possibly because the bride might then become the responsibility of Great Harwood overseers. In April 1789 payments were made for a John Livesey at the workhouse at Tunstead. In August that year this entry was made, ‘To going to the workhouse in order to prevent John Livesey Marriage’ and again on 11 October, ‘To going to Newchurch a second time in order to prevent John Livesey Marrig’.

Reader, it did not work:

Marriage: 22 Oct 1789 St Nicholas, Newchurch in Rossendale, Lancashire

John Livesey – Tunstead in this Chapelry

Nanny White – (X), Bacop in this Chapelry

Ordnance Survey Map 1840s showing Tunstead Workhouse.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

https://maps.nls.uk/

The links below take you to the transcriptions for the relevant years.

1757-58 needs to be photographed again and transcribed.