This blog began as an exploration of whether Bridge Street in Great Harwood ever had a bridge. However, it soon diverged into the history of the Cross Axes pub and the lives of several women whose stories have been overshadowed by the men they married. A former tutor once advised my group to “Beware tangents!” but sometimes, these diversions lead to the most interesting discoveries, as was the case here.

https://maps.nls.uk/

‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

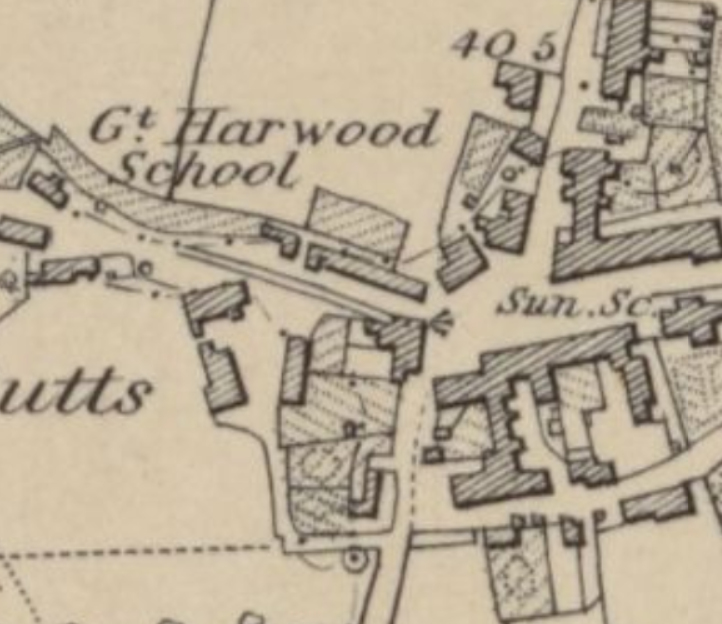

Bridge Street has a unique layout, with two sides separated by a lower-level street and connected only by a series of steps. For years, there has been speculation that the street was named for a planned bridge to connect the two sides. However, the term “bridge” was associated with the area long before Bridge Street was constructed around 1866. In that year, a lease was granted for the houses on the southwestern side of the street, including numbers 2-10 and a joiner’s shop. These were the earliest buildings. Additional leases for numbers 3 and 5-9 were granted in 1897 and 1898, respectively.

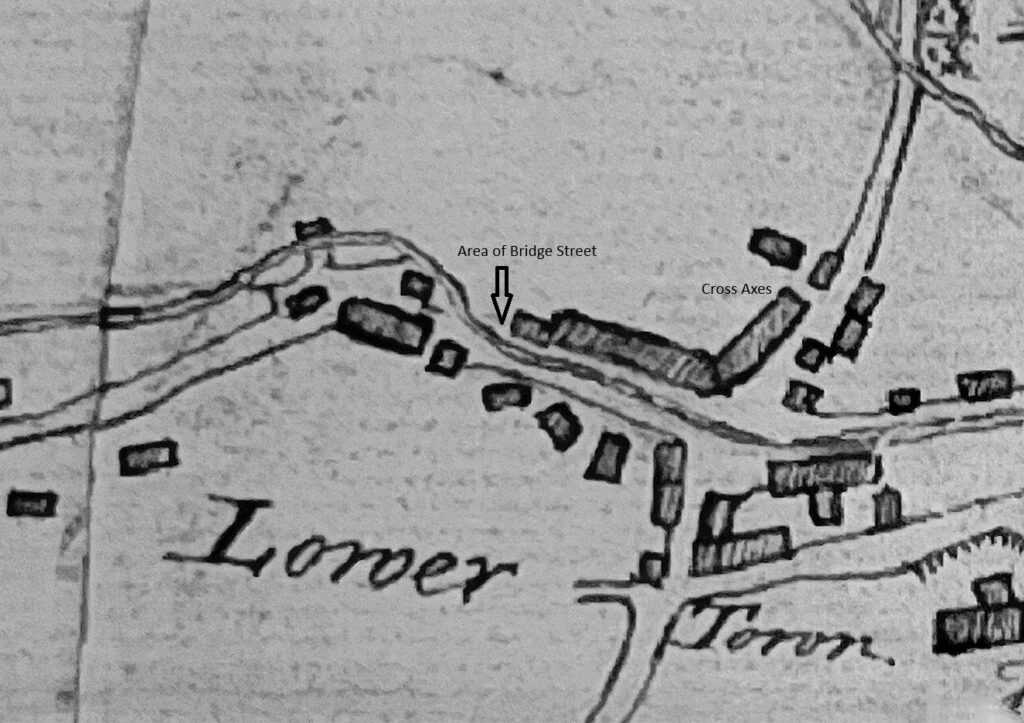

In 1782, a lease for land at Higher Butts on Delph Road described the location as being near buildings called the Bridges. These structures were located near the current steps to Bridge Street. Causeway Brook, now culverted, flows down Delph Road, and it is possible that a small bridge once existed to allow access from the farm south of the stream to the lands north of the brook. However, there is no evidence for this.

The above town plan from around 1796 shows Causeway Brook flowing down Delph Road, across Town Gate, and into Queen Street. There is no indication of a bridge, raising questions about how people and carts crossed the stream. Possible crossing methods include a ford, stepping stones, or a small clapper-style bridge. The first detailed map of the town, the Ordnance Survey map from 1844, shows that the stream had by now been culverted from Delph Road down the length of Queen Street.

https://maps.nls.uk/

‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

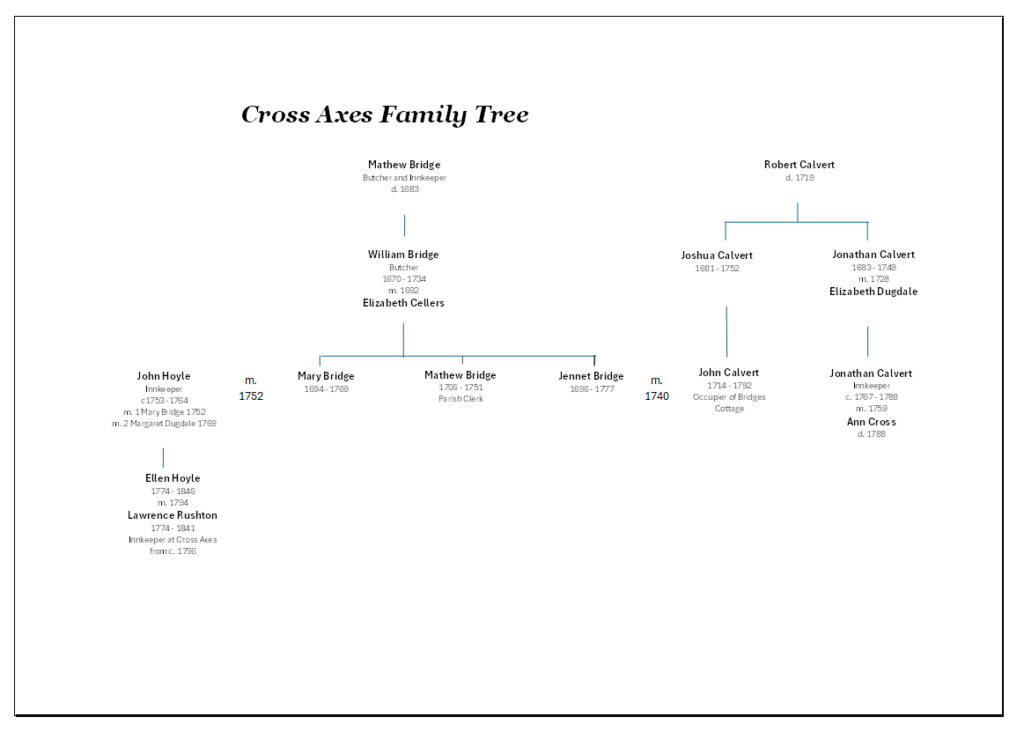

The name Bridge, or Brigg, appears in the town’s parish registers from 1603. One notable individual was Matthew Bridge, who seems to have moved to the town from Whalley and who was a butcher and innkeeper in the town in 1664. His son William was also a butcher, and it is likely he was also an innkeeper although the records that might show this have not survived.

William Bridge had six children: Martha married Richard Standing, a butcher; Margery may have married a John Broadley; Grace doesn’t appear in records after her baptism; Matthew appears not to have married; Mary and Jennet married late in life and it seems these last three children stayed close to home. It was common for women to run inns while men held the licenses, Matthew and William Bridge were butchers, and their wives likely managed the inn and after their parents’ deaths, Mary and Jennet may have run the inn together, with Matthew as the licensee, The poor survival of alehouse records between 1700 and 1740 means we cannot confirm if Matthew was the licensee of the inn, however in 1740 Matthew was paid for ‘rent’ by the overseer of the poor for ‘Duckworth’, showing that he was probably in the business of providing hospitality; over the years other similar payments were made to innkeepers.

When their father died in 1734, neither Mary nor Jennet was married. Mary was about forty, and Jennet was thirty-eight. In 1740, Jennet married John Calvert, who was twenty years her junior. Twelve years later, in 1752, Mary married John Hoyle of Tottleworth Lee in Rishton; she was now fifty eight and he was aged between twenty-eight and thirty-two. William Bridge, the brother, had died in 1751, and it may have become necessary for a man to acquire the inn’s license.

In an era when women often ran inns while men held the licenses, marriages of convenience may have been arranged. A 1754 document shows John Hoyle as the tenant of Matthew Bridge’s tenement, with Mary as a life tenant, and John Calvert as the tenant of Bridge’s cottage, with Jennet as a life tenant and his nephew Jonathan Calvert. Only one other woman, Jane Giles, appears in the list.

From 1753, John Hoyle was listed as the innkeeper. When the Nowells sold the tenement in 1770, John Hoyle bought it, and it was named Matthew Bridge’s tenement on the sale sheet. In 1767, John Hoyle installed Jonathan Calvert, cousin of Jennet’s husband John Calvert, as the innkeeper. By this time, Mary Bridge was about 73 years old and possibly infirm, dying two years later.

It is clear that the building we now know as the Cross Axes was either built or extensively rebuilt in the late eighteenth century and perhaps this was done when John Hoyle bought the tenement.

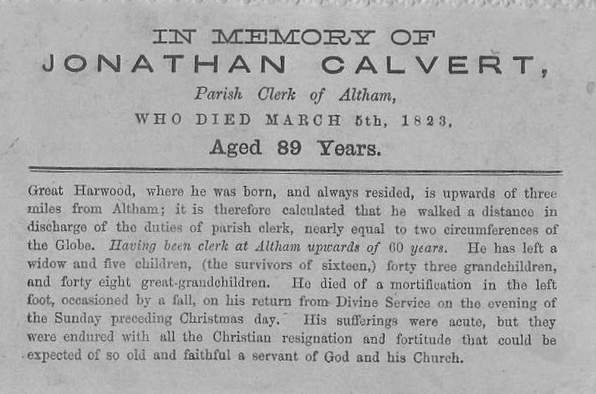

Jonathan Calvert married Ann Cross in 1759. Ann died in April 1788, and in October that year, their daughter Ann married John Aspinall, who was listed as the licensee from 1789 to 1795. Jonathan Calvert lived until 1823, leaving behind numerous descendants and was the sexton of Altham Church for many years. It is unclear what happened to his daughter Ann and her husband John after 1795, but from 1796, Lawrence Rushton was the licensee. John Hoyle had remarried, and his daughter Ellen, by his second wife Margaret Dugdale, married Lawrence Rushton in 1794.

Bridge’s Cottage was still for sale in 1771, with John Calvert listed as the tenant. He died in 1792, leaving his estate to his brother Thomas and nephew Jonathan, but it is unclear if this included the cottage.

As for the Cross Axes, Lawrence Rushton was listed in Baines Directory in 1825 as “victualler and butcher of Cross Axes,” the first recorded use of the name. Lawrence Rushton was buried on March 30, 1841, and from that time, the pub was run by tenants rather than family members. The Hoyles retained ownership until the 20th century.

These notes may explain how Bridge Street and the Cross Axes got their names. Bridge Street likely derived its name from Bridge’s Cottage, and the Cross Axes may have been named after Ann Cross, one of the women who ran the inn. And the notes seem clearly to show that it is evident that these women determined the start and end of tenancies at the inn.They were controlling and managing the running of the inn – their husbands the name on the license, and often busy with their own occupations, butcher, weaver or sexton. When the women retired or died then new tenants were found, even when the husband was still alive and well.

The Women of the Cross Axes

Unknown wife of Matthew Bridge

Elizabeth Cellers – wife of William Bridge

Mary Bridge – daughter of William, wife of John Hoyle

Ann Cross – wife of Jonathan Calvert

Ann Calvert – daughter of Jonathan, wife of John Aspinall

Ellen Hoyle – daughter of John Hoyle, wife of Lawrence Rushton

Leave a Reply